This is a dramatized composite story, based on real timelines, data, and decisions made across the public health landscape. While the main character is fictional, the experiences and pressures she faces were shared by real experts working behind the scenes in March 2020.

PART ONE: Mission Control (March 2020)

Featuring Dr. Lena Patel, Epidemiologist

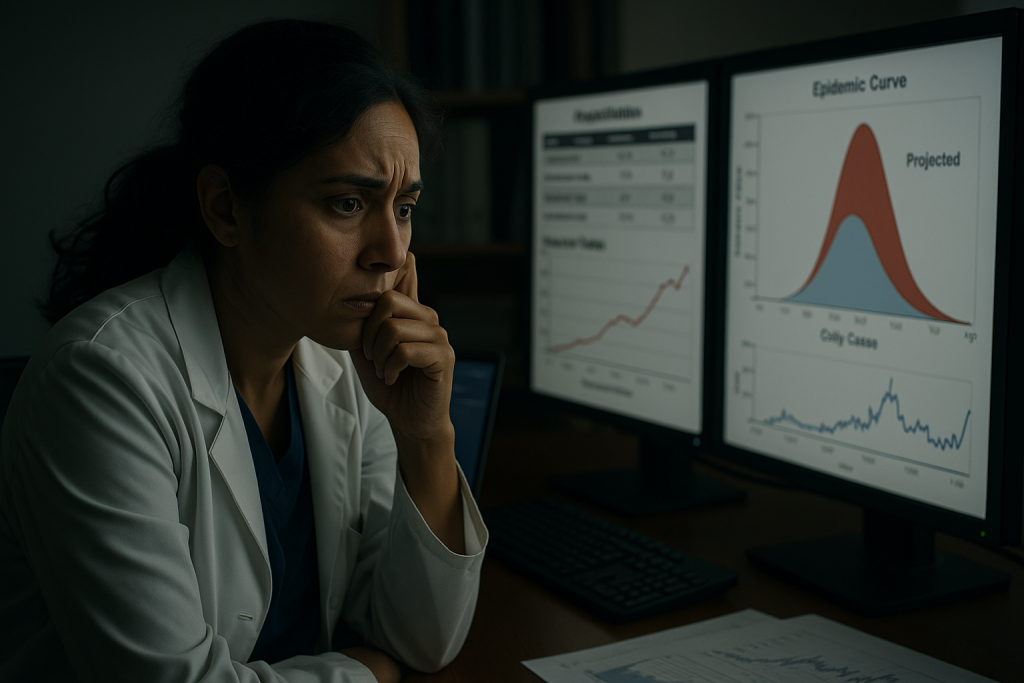

Dr. Lena Patel hadn’t left her desk in six hours.

Her second coffee had gone cold, but the data was very much alive: hospitalization rates from northern Italy, early genomic tracing from Washington State, a spike in unexplained pneumonia cases in Queens, and a blinking red cell in her team’s model labeled:

UNMITIGATED SCENARIO – US: 2.2M DEATHS

She wasn’t guessing. She was modeling.

Lena worked in a state-level epidemiology unit—one node in a quiet, sprawling network of analysts across the country watching a virus gain momentum while most of the public was still focused on the election, spring break, and grocery store shelves.

She and her team didn’t wait for hospitals to fill before acting. They relied on early indicators:

- Syndromic surveillance (people showing symptoms but not yet diagnosed)

- Mobility data from phones and traffic patterns

- Positivity rate curves from a patchwork of local labs

- Population density, health equity metrics, nursing home capacity

- And the reproduction number: R₀, which was higher than anything they’d seen in decades

They fed it all into models to answer a single question:

If people change their behavior now, how many lives can we save?

They ran scenarios. Each hour mattered. Every day of delay meant thousands more infections.

In one model, they found that if they could reduce mobility by 50% and increase masking by 60%, starting immediately, they could cut projected deaths in half.

But how do you ask 300 million people to alter their lives in real time?

The phrase came up in a tense messaging session:

“Two weeks to slow the spread.”

Simple. Urgent. Actionable.

Lena didn’t love it. She knew the curve wouldn’t vanish in two weeks. But they needed people to start behaving differently, fast.

Public health messaging faces an impossible trade-off: nuanced accuracy vs. actionable clarity.

“If we reduce mobility by 50% and increase masking by 60%, we might bend the curve enough to prevent hospital overflow in 6–8 weeks” doesn’t fit on a poster or in a tweet.

It was never a promise.

It was a foothold.

They pushed the message out that night.

She turned back to her screen. The curve was steepening. The clock was ticking.

She hoped someone—anyone—was listening.

PART TWO: The Message Lands, and Fractures

The message was shared tens of millions of times.

Some people canceled plans. Others stayed home, masked up, shifted to remote work. For a few weeks, the curve bent.

But the phrase carried a problem no model could fix.

To public health professionals, “Two weeks to slow the spread” meant:

“If we act now, we buy time—for hospitals, for testing, for lives.”

To much of the public, it sounded like:

“This will be over in two weeks.”

And when it wasn’t—when schools stayed closed, businesses struggled, and the virus kept spreading—the slogan transformed.

What began as a rallying cry turned into a broken promise.

People began to feel deceived. Guidance evolved, as science always does—but from the outside, it looked like backpedaling. Politicians amplified the confusion. Social media filled in the blanks with certainty where public health had left caution.

By summer, the phrase that had been designed to save lives had become a meme. A punchline. A symbol, to some, of overreach or failure.

PART THREE: What It Actually Did

Two months later, Lena pulled up a new dashboard.

This time, it was retrospective: mobility reports, hospitalization curves, behavior surveys, and outcomes plotted against her team’s original projections.

It hadn’t gone perfectly. In some counties, adherence was poor. In others, messaging came too late. The virus still tore through vulnerable communities—especially those already suffering from underfunded care and overcrowded housing.

But even so, the model was clear:

It had worked.

A Nature study published in June 2020 estimated that early non-pharmaceutical interventions—lockdowns, distancing, and yes, public messaging—prevented 3.1 to 3.5 million deaths across just 11 European countries in the first wave alone (Flaxman et al.).

In the United States, analyses from the University of Washington and Imperial College showed that early interventions saved hundreds of thousands of lives, especially in states that moved quickly.

In Lena’s state, their updated model showed:

- Hospitalizations delayed by 19 days

- Peak load reduced by 40%

- Roughly 22,000 lives saved by early behavior changes—driven in large part by that first wave of messaging

It wasn’t enough.

But it wasn’t nothing.

The flattened curve didn’t make headlines.

The hospitals that didn’t collapse weren’t featured in news segments.

The people who lived—quietly, anonymously—would never know they were almost a statistic.

But Lena knew.

And when she looked at the two lines—the one that surged unmitigated and the one that bent just enough—she saw the gap.

That gap was where the message lived.

And where the lives were saved.

Acknowledging the Cost

It’s important to say this out loud:

The messaging worked to save lives.

But it came with real costs.

Businesses closed. Kids fell behind in school. People suffered from anxiety, depression, and isolation. Families were stretched to their limits. Public health officials knew all this—but they had to make impossible choices with incomplete information.

These weren’t decisions made lightly. They were decisions made under fire.

CODA: What We Learned

You’ve heard the slogan. Maybe even mocked it.

But now you know what it was actually meant to do.

It wasn’t a lie.

It wasn’t a promise.

It was a lifeline—hurriedly built, desperately deployed, and caught between urgent action and clear communication.

And even though the message fractured, it held just long enough to save lives.

The lesson isn’t that public health got it wrong.

It’s that crisis communication is harder than anyone imagined.

Next time, we need to be more up-front about what we don’t know and how guidance might change.

Sometimes, in public health, that’s the best you get.

Sometimes, you only know the message worked because the worst didn’t happen.

For Further Reading

Last Updated on June 27, 2025