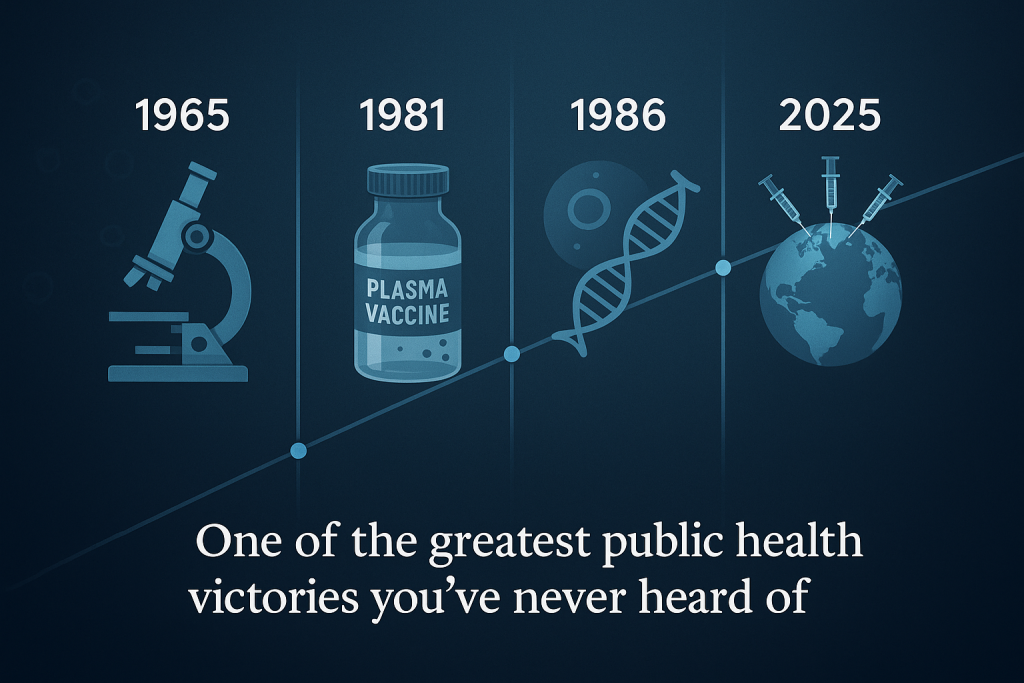

The Cancer Vaccine You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

Part 1: Life with a Hidden Killer

For most of the 20th century, hepatitis B lurked in the background of global health—largely unnoticed, wildly underestimated, and devastating in its consequences.

It didn’t announce itself with sudden outbreaks or dramatic headlines. It didn’t come with paralysis like polio, or rashes like measles. It was quieter than that. Slower. But just as deadly.

Hepatitis B is a virus that infects the liver. Once inside, it can hide there for decades, slowly damaging the organ until—without warning—it fails. Or worse, it turns cancerous.

That’s the horror of hepatitis B: it doesn’t just make you sick. It makes you sick years after you think you’re fine.

And during all that time, you can unknowingly pass it to others—through sex, shared needles, blood exposure, or from mother to child during childbirth. In some parts of the world, nearly every infant born to an infected mother would catch it before their first birthday. And nearly all of them—90%—would carry it for life.

There was no cure. No treatment. Only hope that your liver wouldn’t give out.

By the late 1970s, hepatitis B was killing an estimated 2 million people each year—silently. It was one of the top causes of liver cancer globally. And yet, few people in wealthy countries had any idea it was happening.

In the U.S., it was often associated with stigmatized groups—drug users, sex workers, immigrants—leading to indifference, underfunding, and deep social shame for those who were infected.

You could live half your life with the virus before you knew it was there. And by then, it was often too late.

Part 2: The Quiet Genius Who Cracked the Code

In the 1960s, a physician and geneticist named Dr. Baruch Blumberg was studying a seemingly unrelated mystery: why some populations were more susceptible to certain diseases than others.

He wasn’t looking for hepatitis B.

But while examining blood samples from different groups around the world, he discovered a strange antigen—a marker in the blood that didn’t seem to belong. It showed up again and again in people with liver disease.

It was the hepatitis B virus.

Blumberg’s discovery in 1965 unlocked everything. It made it possible to develop a blood test to detect the virus—a breakthrough that transformed blood transfusions, made it safer for organ transplants, and led to new understanding of liver disease.

But Blumberg didn’t stop there. He wanted to prevent infection entirely.

Working with collaborators, he helped develop the first hepatitis B vaccine—made from the purified blood plasma of infected donors. In 1981, it became the first-ever vaccine approved to prevent a major human cancer.

A few years later, the vaccine was reengineered using cutting-edge biotechnology. Scientists inserted the hepatitis B surface antigen into yeast cells, which produced it in large quantities. The result was a safer, more effective, and more scalable vaccine—the first genetically engineered vaccine in history, approved in 1986.

For this work, Blumberg received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976. In his acceptance speech, he did something unusual for a scientist: he spoke not just of discovery, but of obligation. He believed science had a responsibility to make the world better—and saw vaccines as one of the most powerful ways to do that.

Part 3: A Future Changed Forever

In the decades that followed, the hepatitis B vaccine reshaped global health in quiet, profound ways.

In 1992, the World Health Organization called for universal hepatitis B vaccination of all infants. This was ambitious. Many countries were still struggling to roll out basic immunizations. But the world responded.

By the early 2000s, hepatitis B vaccines were being given to babies within 24 hours of birth—a crucial step to prevent mother-to-child transmission. Three doses during infancy provided over 95% lifetime protection.

The results?

- In countries that adopted the vaccine early, childhood infection rates plummeted.

- In places like Taiwan, where liver cancer had once been the leading cause of death in young adults, childhood liver cancer virtually disappeared.

- Globally, hepatitis B infections in children under five dropped from 10% in 1990 to under 1% today.

- As of 2021, the vaccine had prevented an estimated 1.5 million deaths.

But the success didn’t make headlines. There was no grand eradication day. No viral photo of the last patient. Just lives saved quietly, invisibly, every day.

Afterword: What We Must Remember

Hepatitis B still kills more than 820,000 people each year. 296 million people remain chronically infected, most of them unaware. And in some parts of the world, vaccination rates remain too low—especially in regions affected by poverty, conflict, or misinformation.

But the hepatitis B vaccine shows us what’s possible.

It proves that science can beat cancer—before it even begins.

It shows how global coordination can reach every corner of the world.

It reminds us that prevention doesn’t make headlines—but it saves lives.

Baruch Blumberg once said that science is driven by curiosity, but also by compassion. His discovery gave the world a tool that turned a silent killer into a preventable memory.

The vaccine he helped create is now given to almost every newborn on Earth.

And every time that needle goes in, a different kind of future begins.

Our ‘When The World Got Better’ Series

- When The World Got Better: Smallpox

- When The World Got Better: Polio

- When The World Got Better: Measles

- When The World Got Better: HBV

- When The World Got Better: Hib vaccine

- When The World Got Better: mRNA vaccines

- When The World Got Better: Influenza

Last Updated on June 30, 2025