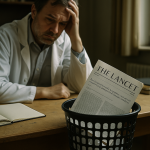

What public health workers endured when the country needed them most

In early 2020, Dr. Michelle Fiscus was the top vaccine official in Tennessee. Her job was to help the public stay safe—especially children. When she released guidance supporting teenagers’ right to get vaccinated (under a longstanding “mature minor” doctrine), the backlash was swift and shocking.

Not long after, she was fired.

Then a muzzle arrived in the mail.

“Someone wanted me to feel threatened,” she said in interviews with CNN and The Tennessean. “And it worked.”

Her story was not unique.

Across the country, dozens of public health leaders were pushed out, silenced, or harassed—not for doing something wrong, but for doing their jobs.

The Numbers Behind the Crisis

According to the National Association of County and City Health Officials, over 500 public health officials resigned or were fired between 2020 and 2021. Most were at the local level—directors of small health departments, school district advisors, regional epidemiologists.

They faced mounting hostility from their own communities.

In Orange County, California, Dr. Nichole Quick was forced to resign after receiving death threats over mask mandates. Protesters showed up at a public meeting wearing images of her face printed with a Hitler-style mustache. They even shared her home address.

“I Never Thought I’d Need a Security Detail”

Dr. Amy Acton, Director of the Ohio Department of Health, was widely praised early in the pandemic for her clear communication and calm leadership. But as shutdowns extended and misinformation spread, the praise turned to rage.

Protesters carrying assault rifles marched outside her house. She received threatening messages online and in person. Eventually, she resigned from her position.

“They don’t even know me,” she told The New York Times. “But they’re yelling that I’m evil. That I’m part of some plot. I’ve spent my whole life in public service.”

The Toll Wasn’t Just Professional

A CDC survey of more than 26,000 public health workers in 2021 found that over half reported symptoms of at least one mental health condition, including PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

In California’s Humboldt County, health officer Dr. Teresa Frankovich publicly described her decision to step down in 2020:

“The hate mail became routine. The accusations, the anger—it just didn’t stop. It wore me down.”

She wasn’t alone. Local officials across Montana, Colorado, Missouri, Texas, Florida, and Michigan shared similar experiences in interviews with local news outlets—burnout mixed with fear, not from the virus, but from the people they were trying to protect.

Why Did This Happen?

Part of the answer is psychological.

When people are afraid, they seek control. And when the truth is complex, conspiracy theories offer simpler villains.

- Confirmation bias made many people reject uncomfortable facts.

- Disinformation on social media reinforced tribal identity.

- And the illusion of expertise—the Dunning-Kruger effect—led people to think they understood public health better than trained experts.

They Showed Up Anyway

Even as they were harassed, threatened, and demoralized, most public health workers kept showing up.

In New Mexico, health department staff worked 12-hour days distributing vaccines to remote communities, despite staff shortages and personal risk.

In Kansas, local officials drove hundreds of miles to deliver PPE when supply chains failed.

They weren’t in it for fame. Many made less than teachers. Some worked without hazard pay. They did it because they cared.

We Can’t Afford to Forget This

The pandemic exposed just how fragile trust in public institutions has become. But it also showed something else:

The people who protect our public health aren’t faceless bureaucrats. They’re neighbors. Parents. Dedicated professionals who often suffered in silence.

And if we want to be better prepared next time, we need to remember what they endured—and why.

“We weren’t perfect,” Dr. Fiscus said in a 2022 interview. “But we were trying. We were trying to save lives. And some of us paid a steep price for that.”

If this moved you, share it.

Because the next time crisis strikes, the truth needs more than silence—it needs us.

Last Updated on June 26, 2025