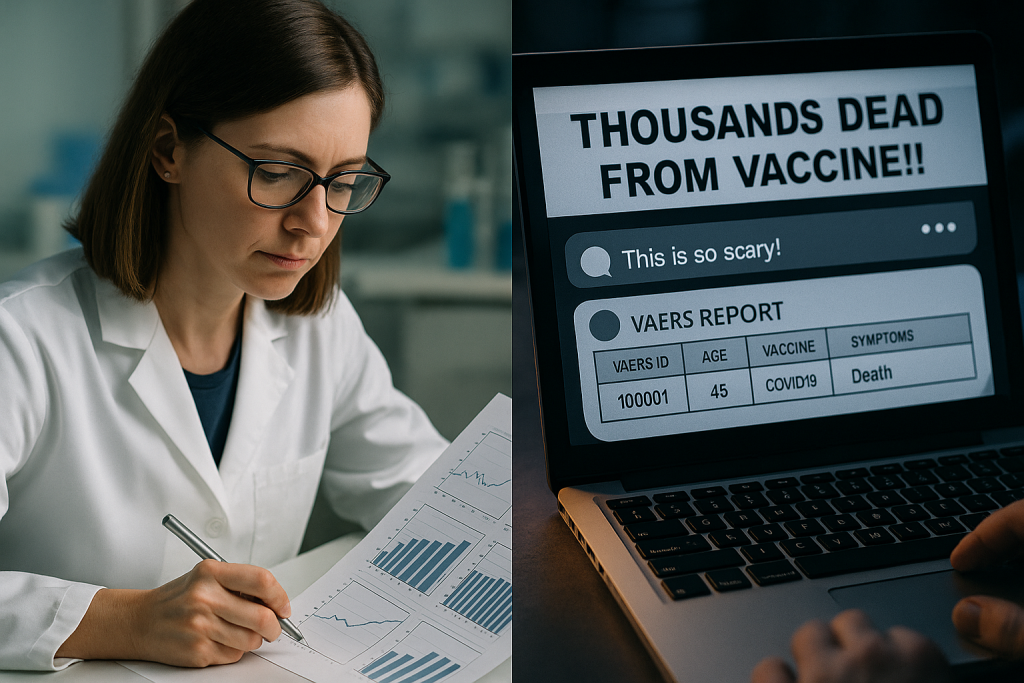

“Thousands of people have died from the COVID vaccine!”

You’ve probably seen that claim online. It usually comes with a screenshot of a number from something called VAERS—the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System. It looks official. The number is big. The tone is ominous.

But here’s the thing:

That number doesn’t mean what people think it means. Not even close.

What Is VAERS, Really?

VAERS was created in 1990 by the CDC and FDA as a safety signal system. Think of it like a public suggestion box for vaccines—where anyone can submit a report.

Got a rash after your flu shot? Submit it. Felt dizzy after your COVID booster? Report it.

Heard your neighbor’s cousin’s friend had a seizure? Technically, you can submit that too.

The idea isn’t to create a verified, curated list of real vaccine injuries.

The idea is to cast a wide net—to catch any early patterns that might suggest a real issue.

But that openness comes at a cost:

VAERS reports are unverified. They’re not proof of causation. And they were never meant to be used to “count” vaccine injuries.

Even the VAERS website warns:

“VAERS reports alone cannot be used to determine if a vaccine caused or contributed to an adverse event.”

Yes, People Really Misuse It That Badly

Here’s a wild example: in 2004, a doctor named James Laidler submitted a completely fake VAERS report saying the flu vaccine turned him into The Incredible Hulk.

It was accepted.

Why?

Because VAERS doesn’t filter submissions on the front end. It’s not meant to. It’s a starting point for investigation, not a scientific conclusion.

But online? It’s become something else:

A raw database of anecdotes twisted into conspiracy fuel.

The Psychology Behind the Mistake

Why does VAERS feel so compelling to people who are already skeptical?

It comes down to a few tricks our brains play on us:

- Confirmation Bias: Once you suspect vaccines are dangerous, you start seeing “proof” everywhere—even in ambiguous data.

- Availability Bias: Dramatic stories stick with us more than boring data. “This guy got vaccinated and died in his sleep” is way more memorable than “millions got vaccinated and nothing happened.”

- Post Hoc Fallacy: People assume that if something bad happened after a vaccine, the vaccine caused it. But correlation is not causation.

So What Does the Real Science Say?

Here’s the part conspiracy theorists conveniently leave out:

COVID vaccines are some of the most studied medical interventions in human history.

Over 13 billion doses have been administered worldwide. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines each went through large, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials—the gold standard in medicine.

Do vaccines have side effects? Yes—some people get sore arms, fatigue, or fever.

Are there rare serious risks? Yes—like myocarditis in young men, at a rate of about 1 in 50,000 to 100,000, usually mild and recoverable.

But what do the numbers show?

- In the U.S., the CDC’s VSD system (which does verify events) shows an extremely low rate of serious vaccine complications.

- The benefits of vaccination—preventing hospitalization, long COVID, and death—far outweigh those rare risks.

- In fact, most studies suggest the risk of myocarditis is higher from getting COVID itself than from the vaccine.

Why the Confusion Matters

When people misuse VAERS to spread fear, they don’t just misinform.

They cause real harm:

- People delay or avoid vaccination.

- Lives are lost to preventable illness.

- Trust in public health institutions erodes.

All because we’ve misunderstood a tool designed to protect us.

Let’s Ground Ourselves in Reality

Here’s the truth:

- VAERS is an important part of vaccine safety monitoring—but it must be interpreted by experts, in context, with follow-up investigation.

- Vaccines are studied rigorously before and after approval—using randomized trials, verified databases, and global monitoring systems.

- Fear spreads faster than facts, but you can choose to be part of the signal, not the noise.

The Bottom Line

The next time someone sends you a VAERS screenshot, ask them this:

“Do you know what VAERS is actually for?”

Because when we let anecdotes outweigh evidence, we lose sight of the truth—and the lives it could save.

Last Updated on June 26, 2025