Part 1 of 3: Why vaccine risk comparisons miss the point entirely

About this Series

This article is part of a series designed to help readers think clearly and calmly about vaccines. In an age of misinformation and overwhelming noise, we aim to cut through the confusion with evidence, reason, and empathy. Whether you’re vaccine-hesitant, curious, or just want to make informed choices for your family, this series is here to offer clarity—grounded in science, not fear.

- Part I – You’re Asking the Wrong Question

- Part II – Not All Risks are Equal

- Part III – You’re Not Alone in This Fight

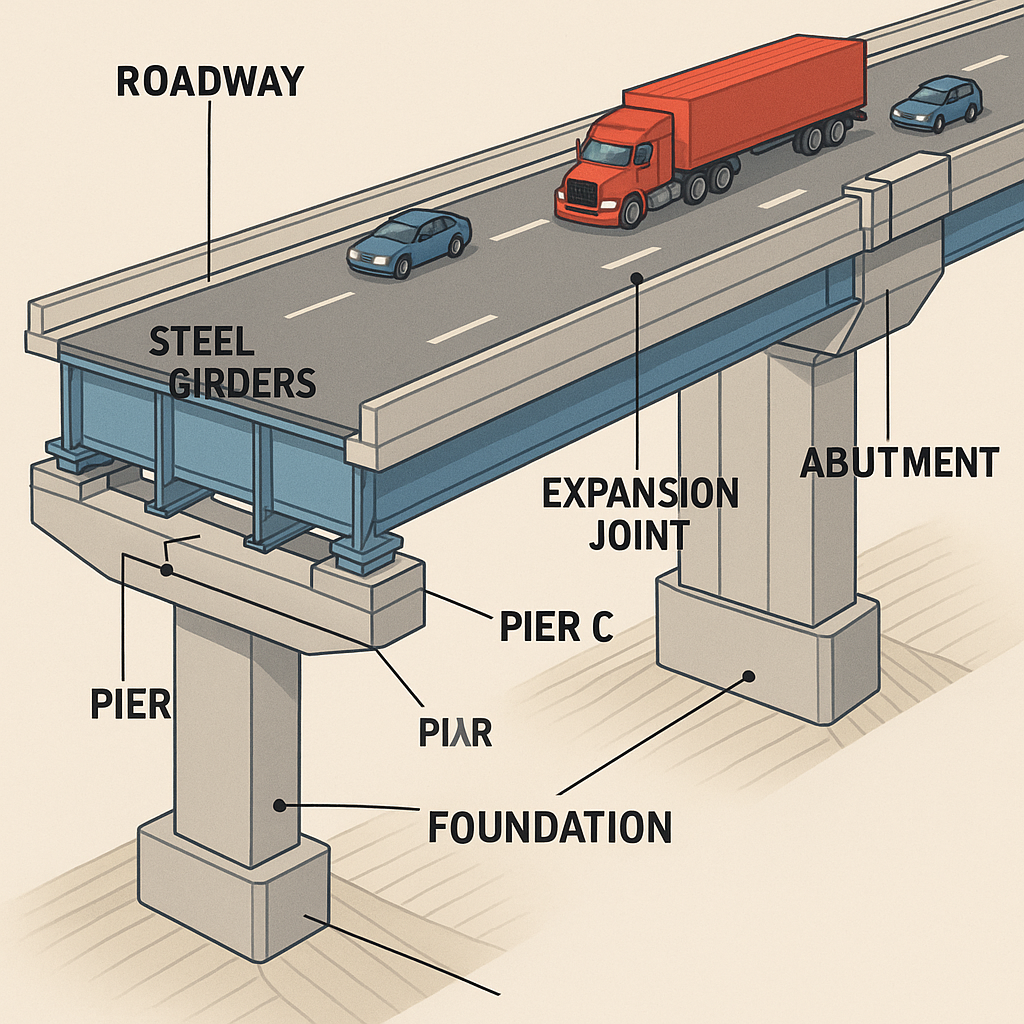

🚗 The Seatbelt Fallacy

Imagine you’re heading out for a drive and say to yourself:

“I probably won’t get into a crash today—and seatbelts can bruise your ribs. So I’ll skip it.”

That’s technically true. But it’s also a really bad decision.

Because the right question isn’t:

“What’s the chance I crash?”

or

“What’s the chance my seatbelt hurts me?”

The right question is:

“If something goes wrong, how much worse—or better—off will I be depending on whether I wore the seatbelt?”

And that, right there, is the same mistake people often make when deciding whether to get a vaccine.

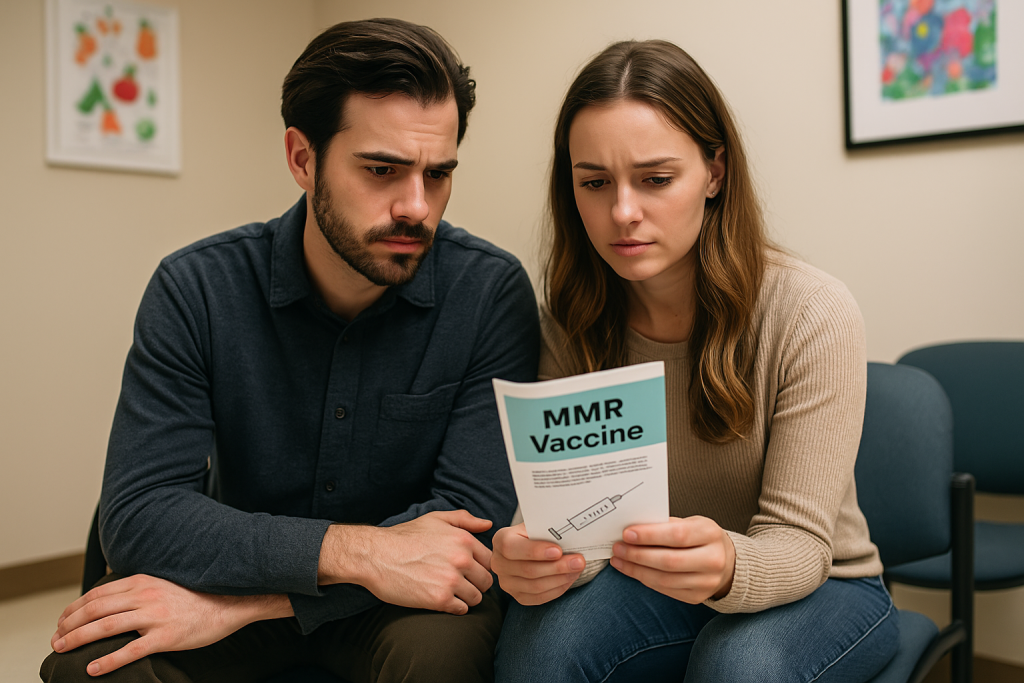

💉 Vaccine Risk vs. Disease Risk: A False Comparison

A lot of vaccine skeptics approach the question like this:

- “What are the chances I get measles?”

- “What are the chances I have a bad reaction to the MMR vaccine?”

Then they compare the two.

But that’s like comparing two separate coin tosses and whether or not to take a vaccine is one choice. It misses the fact that vaccination changes the odds of the first one happening—and, more importantly, it doesn’t even ask the right question.

The question you should ask is:

“How much more or less likely is it that something bad will happen to me if I take this shot?”

It’s not a question of absolute risk. It’s a question of net change in your overall risk of harm.

🧠 Risk 101: Combine, Don’t Compare

Let’s get a little geeky for a second. When you’re evaluating a medical choice, you need to consider:

- The probability that something bad happens

- The severity of that bad thing

- How much your action changes that outcome

In math terms, we call this expected harm:

Probability × Impact

It’s the same principle insurance companies use when calculating premiums, and casinos use to ensure the house always wins.

🧪 Example: Measles vs. the MMR Vaccine

Let’s say you’re thinking about skipping the MMR vaccine. Here’s how the actual numbers stack up.

If You Don’t Vaccinate:

- Chance of catching measles during an outbreak if unvaccinated: ~90%1

- Chance of serious complication (like brain swelling): 1 in 1,0002

- Chance of death: 1 to 2 in 1,0002

If You Do Vaccinate:

- Chance of serious vaccine reaction (e.g., seizure): ~1 in 40,0004

- Chance of fatal reaction: ~1 in a million4

Result:

Your total expected harm is significantly reduced by taking the shot. It’s not even close.

And that’s before considering herd immunity, missed school/work, hospital bills, or long-term complications.

📆 The Myth of “Low Risk”

Some people say, “I’m not likely to get this disease, so why bother with the vaccine?”

It’s a common way of thinking—but it leaves out one big piece of the puzzle: how long you plan to stay unvaccinated.

When you skip a vaccine, you’re not making a one-time decision. You’re saying “I’m going to take my chances, every day, for the foreseeable future.”

Even if there’s no outbreak right now, that doesn’t mean you’re safe forever. Outbreaks happen. People travel. Vaccination rates drop. And every time that happens, you’re back in the danger zone.

Meanwhile, the risk of a serious vaccine reaction? That’s a one-time risk per dose. Whether it’s a single shot or a series of boosters, each dose gives your immune system the tools it needs to protect you. The benefit builds over time, while the risk doesn’t stack the same way.

So the real question isn’t “What are the chances I get sick today?”

It’s “How many chances am I giving this disease to hurt me over the next few years?”

Skipping the vaccine isn’t avoiding risk. It’s prolonging it.

🧠 Why Our Intuition Fails

Our brains are wired to make fast, emotional decisions—not rational calculations. That’s why so many people fall into these traps:

1. Availability Heuristic

Rare but vivid stories (like a supposed vaccine injury) feel bigger than invisible threats like polio outbreaks.

2. Omission Bias

We feel worse about doing something that leads to harm than not doing anything—even if the harm from inaction is greater.

3. Affect Heuristic

We judge risk by emotion, not numbers. If it feels scary, we think it’s riskier—even when the data says otherwise.

🧬 A Second Look: COVID Edition

Let’s apply this risk math to a disease we all remember: COVID-19.

💥 If You’re Unvaccinated:

Let’s imagine 100,000 unvaccinated young adults:

- 🦠 Nearly all will eventually get COVID → ~100,000 infections

- 🏥 About 1–5% need hospitalization6

→ 1,000 to 5,000 end up in the hospital - 🧠 Some develop long COVID or permanent complications

→ Estimates vary, but let’s say 2,000+ suffer long-term effects - ⚰️ And while deaths are rare in young people, some still die

💉 If You’re Vaccinated:

Now let’s look at 100,000 vaccinated young adults:

- 🩹 Serious vaccine side effect:

→ Fewer than 1 person in 100,000 (most mild effects don’t count here) - 🦠 Many still get infected, but…

→ Hospitalization drops by 90% or more

→ Only 100–500 hospitalized

→ Long COVID risk drops dramatically

→ Perhaps a few hundred, not thousands

That’s thousands of hospital beds saved, lives protected, and long-term suffering avoided.

🧠 Bottom Line:

| Outcome | Unvaccinated (per 100k) | Vaccinated (per 100k) |

|---|---|---|

| Infections | ~100,000 | ~100,000 |

| Hospitalizations | 1,000–5,000 | 100–500 |

| Long COVID (est.) | ~2,000+ | < 500 |

| Serious vaccine reactions | N/A | < 1 |

Even with milder variants today, vaccines continue to lower your odds of serious harm—especially for people with asthma, diabetes, or other risk factors.

🧠 Rational Risk Isn’t Cold—It’s Compassionate

We do this kind of risk math every day:

- We wear seatbelts, even if we haven’t crashed in years

- We buy insurance for homes that never burn down

- We carry an umbrella because maybe it will rain

It’s not because we’re paranoid. It’s because we’re minimizing the total harm we might face over time.

Vaccination works the same way. It’s a safety belt for your immune system—and for your community.

👉 Coming Up Next: Not All Risks Are Equal

So far, we’ve treated “bad outcomes” like they’re all the same. But we know that’s not true.

In Part 2, we’ll explore:

- Why a fever isn’t the same as encephalitis

- How to weight different risks based on severity

- Why vaccines win even harder when we include impact—not just probability

Stay tuned—and geek out with us as we dig even deeper.

🧠 Final Thought

Vaccines aren’t a gamble. They’re one of the safest bets we’ve ever made in public health.

When we zoom out, run the numbers, and think clearly, the math points in one direction:

You’re safer with the shot.

This is why all of the major health organizations around the globe recommend vaccinations. They’ve done the math so you don’t have to. So if you’re on the fence—or know someone who is—ask them gently:

“What are you actually comparing?”

Because chances are, they’re asking the wrong question.

- CDC Measles Transmission ↩︎

- CDC Measles Complications ↩︎

- CDC Measles Complications ↩︎

- CDC Vaccine Safety ↩︎

- CDC Vaccine Safety ↩︎

- CDC – COVID-NET hospitalization rates ↩︎

Last Updated on July 15, 2025