During the pandemic, a surprising number of well-informed, well-educated people misjudged the risks of COVID.

It wasn’t because they were careless, or unintelligent, or uninformed. It’s because human beings aren’t naturally good at understanding probability. Most of us aren’t trained to think statistically. We rely on intuition. And intuition is often a poor guide when the stakes are invisible, fast-moving, and communal.

Let’s unpack what went wrong—and how we can think better next time.

📊 We’re Not Wired for Statistics

The human brain evolved to make quick decisions with limited information. That’s useful when avoiding predators or making gut decisions in a conversation.

But in a pandemic? It becomes a problem.

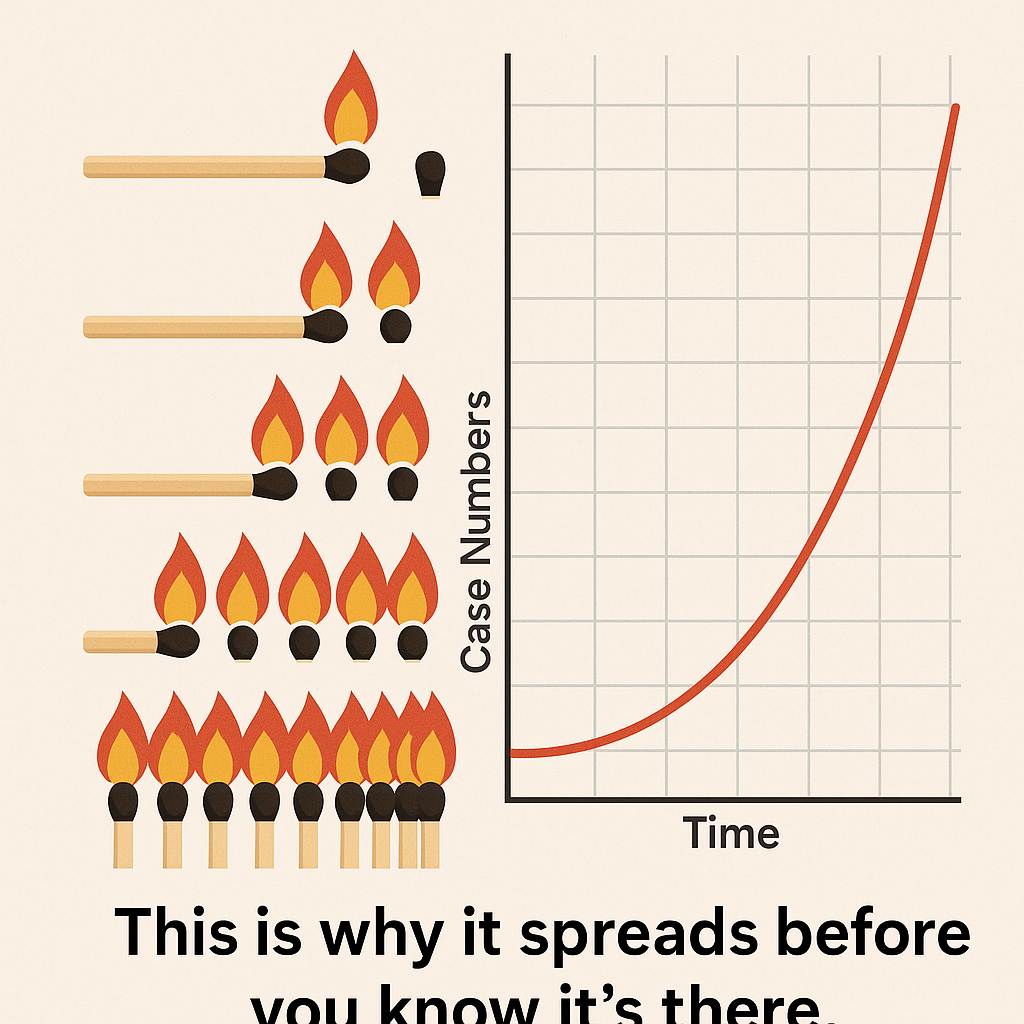

We tend to overestimate risks that feel vivid or emotional (like vaccine side effects) and underestimate risks that are abstract or delayed (like spreading COVID without knowing we’re infected). We also struggle to grasp exponential growth, which is how viruses spread—doubling, not adding.

Understanding risk in a pandemic requires thinking like a population, not just a person. That’s not how most of us are taught to reason.

🧍 “I’m Young and Healthy” Was Never the Whole Story

Many people thought about COVID risk in purely personal terms:

“I’m low risk. If I catch it, I’ll probably be fine.”

That might have been statistically true for a healthy individual. But pandemics don’t unfold based on individual odds. They unfold through chains of transmission.

Even if you were unlikely to get seriously ill, the people you could unknowingly infect might not be so lucky: elderly relatives, coworkers with chronic conditions, strangers on the bus.

Your personal risk may have been low—but the collective impact of thousands of low-risk people getting infected was extraordinarily high.

🌍 Community Transmission Was Hard to See—Until It Was Everywhere

One of the hardest concepts to communicate during the pandemic was that the risk wasn’t static. It changed constantly, depending on how much virus was circulating in the community.

When cases were rising, the safest-seeming spaces could suddenly become risky. And because COVID spreads before symptoms appear, people often assumed they were safe because they felt fine.

By the time the risk felt real, the virus had already moved through communities. That’s the nature of exponential spread: it’s easy to miss, right up until it isn’t.

⚖️ Vaccine Side Effects Seemed Scarier Than the Virus Itself

Here’s another way our instincts failed us: when the vaccines came out, many people fixated on extremely rare side effects—like blood clots—without comparing them to the much more likely risk of getting COVID itself.

This isn’t irrationality—it’s psychology. We react more strongly to stories that are dramatic, unusual, or emotionally charged. The rare side effect feels more “real” than the statistical threat of a virus we can’t see.

But in truth, the risk of a serious reaction to a COVID vaccine was far smaller than the risk of hospitalization—or death—from COVID. And unlike COVID, we could predict and prevent the vaccine risk.

🎓 Intelligence Doesn’t Guarantee Good Risk Assessment

This wasn’t just a problem among people who rejected science outright. Even thoughtful, educated people made poor choices—because being smart doesn’t mean you naturally think in terms of public health, probability, or systems.

We all carry cognitive biases. And in a high-stress, high-uncertainty situation like a pandemic, those biases often take over—no matter how educated we are.

🧠 What We Can Learn

We don’t need everyone to become an epidemiologist. But we can do better if we remember a few basic ideas:

- Personal risk is not the same as public risk.

- Risk isn’t binary—it changes with context.

- Low-probability events can still cause enormous harm when repeated across a population.

- Protecting others sometimes means acting before the danger is visible.

If we internalize these lessons, we’ll be better prepared—not just for the next pandemic, but for any challenge that requires collective thinking and shared responsibility.

💡 If this helped make things clearer, consider sharing it.

You might help someone else think more clearly too.

Last Updated on June 27, 2025