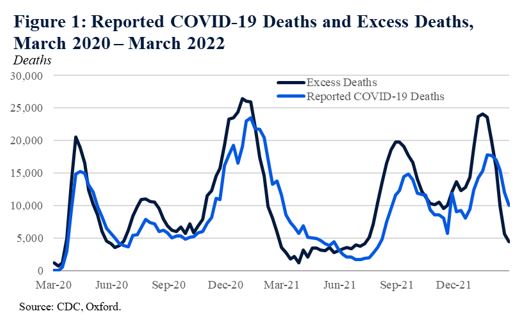

By the end of 2020, something had happened that no conspiracy could dismiss: people were dying. A lot of them. In numbers far beyond what we normally see.

There were more funerals. More obituaries. More empty chairs at dinner tables. And even in countries where COVID testing was sparse, and medical systems were overwhelmed, something grim stood out in the data—a massive spike in total deaths.

This is what epidemiologists call “excess deaths”—and it’s one of the most powerful tools we have to cut through misinformation, noise, and denial.

🧮 What Are Excess Deaths?

Excess deaths are the number of deaths above what we would normally expect in a given time period, based on previous years’ data.

Let’s say a country typically sees 100,000 deaths in the first half of the year, based on five-year trends. If that same country sees 135,000 deaths during the same timeframe in 2020, that’s 35,000 excess deaths.

These numbers aren’t affected by how COVID deaths are coded, whether someone was tested, or even whether they died with or of COVID. It’s just this: more people are dying than usual, and something is causing it.

In 2020 and 2021, those spikes were global. Not just in the U.S. Not just where the media was watching. Everywhere.

🧠 Why Conspiracies Can’t Explain It Away

Many conspiracy theories claim doctors “labeled every death as COVID to make money,” or that we only counted people who “died with COVID” and not necessarily from it.

But here’s the problem:

Even if you removed every single official COVID death from the record… the spike in total deaths is still there.

It’s visible in countries with robust testing.

It’s visible in countries without robust testing.

It’s visible even when you strip away everything we think we know about the pandemic.

There is no plausible alternate explanation for millions of people dying above expected trends—except the emergence of a new, deadly virus.

🎬 Blame Hollywood (Sort of)

For decades, our idea of a “serious pandemic” has been shaped by movies like Outbreak, Contagion, and even The Walking Dead.

In those stories, viruses are instantly fatal, with death rates of 70%, 90%, or more. People bleed from their eyes or drop dead within hours. So when COVID came along, with a death rate closer to 1%, it felt underwhelming by comparison.

But real pandemics don’t work like the movies.

They don’t have to kill everyone to be devastating.

They just have to spread far enough and fast enough.

And that’s exactly what COVID did. With millions of deaths worldwide and tens of millions more left with long-term complications, it became the most serious global health crisis in a century—not because it was the most lethal virus, but because it was one of the most widespread.

🧩 The Psychology Behind the Doubt

It’s tempting to believe that something so disruptive had to be exaggerated or engineered—especially when we’re surrounded by social media posts that suggest “no one really died.”

But this is availability bias at work. If you didn’t personally know someone who died—or didn’t see the worst-hit hospitals on TV—you might feel like the threat was overblown.

That’s why data matters. It shows us what our emotions or social bubbles might miss.

🔍 The Bottom Line

You can debate policy. You can question how governments responded. But the numbers don’t lie:

Millions more people died during the COVID years than we would expect—no matter how you count.

That’s not hype. That’s not politics. That’s not media spin.

That’s excess deaths. And it’s one of the clearest signals we have that something went terribly wrong.

🧠 Want to Learn More?

Here are a few places you can explore further:

- CDC Excess Deaths Tracker

- The Economist COVID Excess Mortality Model

- Our World In Data – Excess Mortality

Last Updated on June 26, 2025