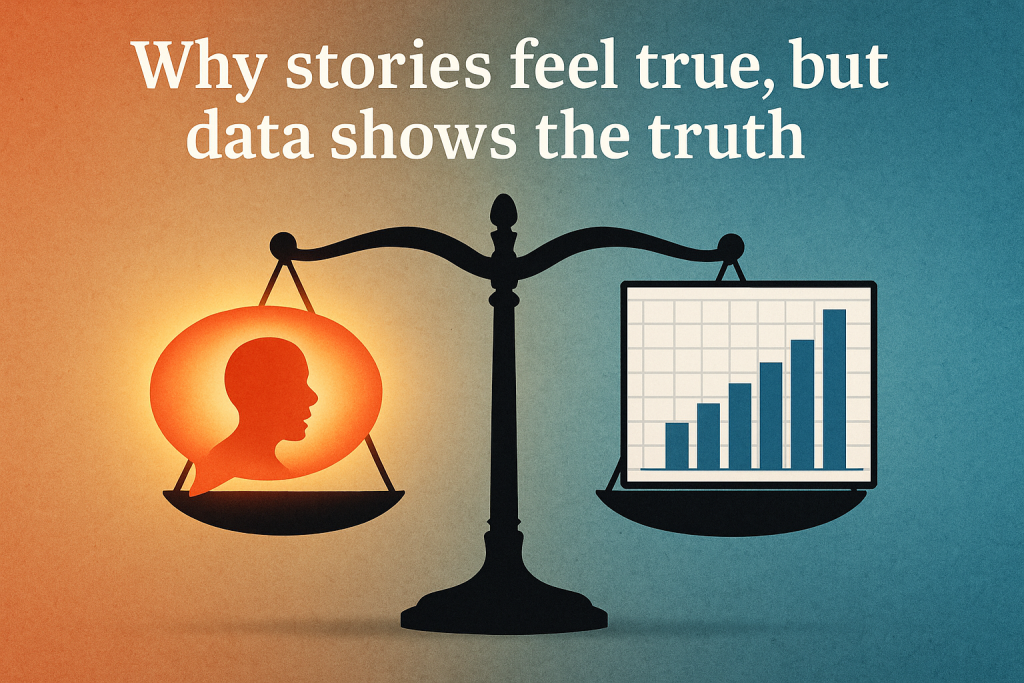

This is part of our “Come Geek Out With Us” series, where we dig deeper into how science works—not just what the headlines say. Today we’re exploring why stories feel more real than statistics, and what that means for how we talk about health.

The Anecdote That Sticks

We’ve all heard it:

“My cousin got the COVID vaccine and had heart palpitations that night. She’s convinced it was from the shot. Honestly, that freaked me out.”

That kind of story hits hard. It’s vivid. It’s real. You know the person. It stirs emotion in a way that no bar graph ever will.

And that’s exactly the problem.

Your Brain Is Wired to Trust Stories

Humans evolved to learn through stories. They’re easy to remember, emotionally powerful, and neurologically sticky. In psychology, this is called the availability heuristic:

We tend to overestimate the likelihood of things we can easily recall.

So when you hear about someone having a bad reaction—even if it’s rare—your brain stores that story in the “this could happen to me” file. But when you hear that only 0.001% of people experienced that effect in a clinical trial? It barely registers.

👥 Meet the Minds Behind the Bias

This concept—and much of what we know about how our brains misjudge risk—comes from the groundbreaking work of two Israeli psychologists: Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

In the 1970s, the pair revealed that humans don’t make decisions like calculators. Instead, we use mental shortcuts called heuristics—fast, intuitive rules of thumb that usually help, but sometimes mislead.

The availability heuristic is one of their best-known contributions. It explains why emotionally powerful events (even if rare) feel more important than common, boring ones.

Their work reshaped psychology, economics, and public health. Kahneman later won the Nobel Prize in Economics, and their story was chronicled in Michael Lewis’s best-selling book The Undoing Project.

Their key insight: Even smart people are predictably irrational. And when we understand how, we can do better.

But Here’s the Thing About Anecdotes

Anecdotes tell us that something happened.

They don’t tell us how often it happens—or whether the vaccine caused it.

In medicine, what we really care about is the base rate:

- How often does this thing happen normally, with or without the vaccine?

- Is the rate higher after vaccination than before?

- Is it higher in vaccinated people than in unvaccinated ones?

The Base Rate Fallacy, Explained Simply

Let’s say you hear that someone had a seizure the day after getting vaccinated.

That sounds scary, right?

But what if:

- 1 in 10,000 people have a seizure every day anyway, and

- You just gave 10 million people the vaccine in one week?

Math check: 10,000,000 ÷ 10,000 = 1,000

You’d expect 1,000 seizures that week just by coincidence.

So the question becomes: Was that number higher than usual?

If not, there’s no signal—just noise.

This is the kind of thinking that helps scientists separate correlation from causation.

Real Example: Myocarditis in Young Men

Let’s be honest: Some vaccine side effects are real.

Take myocarditis (inflammation of the heart) after mRNA COVID vaccines—especially in young men. Researchers noticed a small increase in cases shortly after second doses. Instead of dismissing it, they investigated.

- They compared rates in vaccinated vs. unvaccinated people

- They tracked timing, severity, and recovery

- They published the results, adjusted recommendations, and prioritized transparency

Most cases were mild, and full recovery was the norm.

But the signal was real—and action was taken.

That’s how science should work: watch closely, ask questions, follow the data.

Why Social Media Makes This Harder

The internet runs on emotion. Algorithms are designed to reward content that provokes fear, anger, or awe—especially if it’s short, personal, and dramatic.

That means:

- One alarming anecdote can spread faster than any public health report

- Emotional stories drown out statistical context

- People start making decisions based on fear, not evidence

And the result? A distorted picture of reality.

So What Does Science Do Instead?

Instead of relying on personal stories, scientists:

- Run randomized trials to compare outcomes directly

- Monitor huge populations over time

- Use confidence intervals to express uncertainty

- Look for patterns, not isolated events

It’s not flashy. It’s not viral. But it works.

If the plural of anecdote were data, Facebook would be the most accurate public health institution in the world.

(Spoiler: it’s not.)

Be Empathetic—But Think Bigger

This doesn’t mean we should mock or dismiss people who’ve had bad experiences. Their stories matter. But individual stories are just starting points, not endpoints.

Science is about asking, “Is this a pattern?”

And that requires data.

The Bottom Line

Stories feel true. Data test what’s actually true.

When you’re trying to understand your health—or the health of millions—trust the signal, not the noise.

Your cousin’s experience deserves compassion.

But when it comes to making decisions for yourself and your family, look at the full picture.

Let the story move you.

Then let the data guide you.

📚 Want to Go Deeper?

If you’re intrigued by the psychology behind how we think—and how often we get it wrong—these books are essential reading:

- 🧠 Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

A Nobel Prize–winning exploration of the two systems that drive our thinking: the fast, intuitive one, and the slow, rational one.

👉 Read on Amazon - 👬 The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis

A compelling biography of Kahneman and Tversky’s unlikely friendship and the brilliant, often emotional journey that changed how we understand human judgment.

👉 Read on Amazon

These aren’t just books about psychology. They’re books about us.

Last Updated on June 30, 2025