The Long Road to a Life-Saving Vaccine

😢 Before the Vaccine: A Summer of Fear

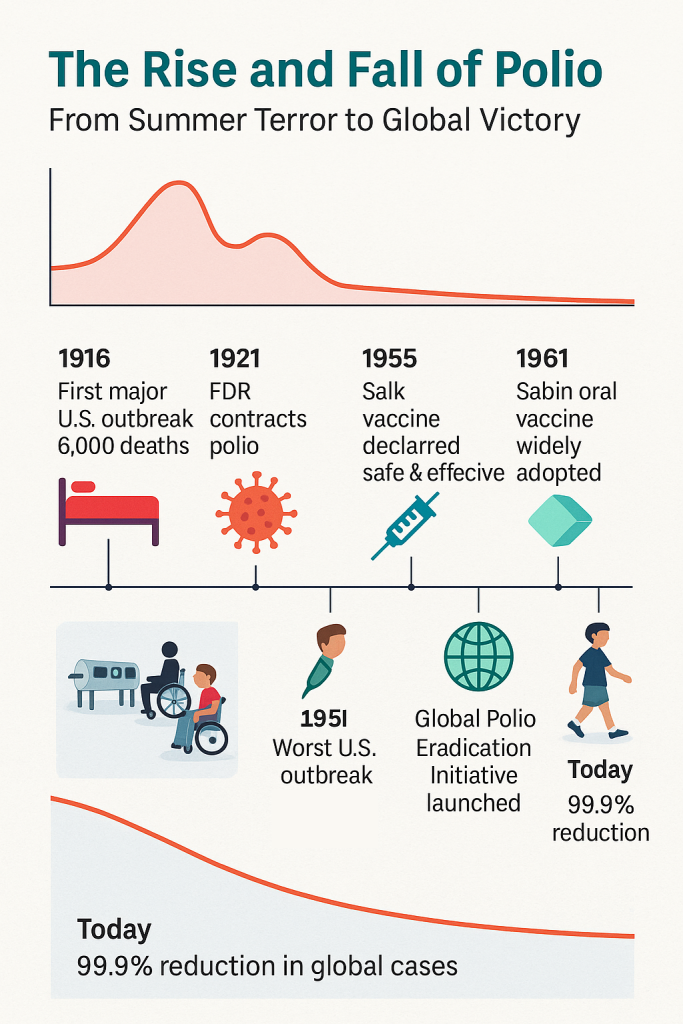

For much of the 20th century, summer didn’t just bring sunshine—it brought fear. Every year, like clockwork, outbreaks of poliomyelitis, or polio, would surge through towns and cities, paralyzing tens of thousands of children. Parents were terrified. Public swimming pools were shut down. Movie theaters emptied. Playgrounds went silent.

And the scariest part? No one knew who would be next.

Polio is caused by a virus that spreads silently—often through water or contact with feces. Most infected people never show symptoms. But in a small percentage of cases, the virus invades the nervous system and causes irreversible paralysis. Legs stopped working. Arms hung limp. Some children lost the ability to breathe on their own.

“It was like a storm. One day your child had a fever, and the next day, she couldn’t walk,” recalled one parent in a 1950s newspaper interview.

In the U.S., 1952 was the worst year on record, with nearly 60,000 cases and over 3,000 deaths. Hospitals overflowed with children in leg braces, crutches, and iron lungs—large machines that helped them breathe after their chest muscles stopped working.

No one was safe. Even President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who led the country through the Great Depression and World War II, had been paralyzed by polio in his late 30s. He hid the extent of his disability from the public, but his struggle helped galvanize national attention.

Polio wasn’t just a disease. It was a thief—stealing childhoods, mobility, and lives.

👨🔬 The Race to a Vaccine

By the 1940s, scientists were racing to find a solution. Funding poured in from millions of Americans through the March of Dimes, a grassroots campaign that encouraged people to send in small donations—literally dimes—to support polio research.

It worked. By the early 1950s, polio research had more public funding than any other non-military scientific project in U.S. history.

Enter Dr. Jonas Salk, a virologist working at the University of Pittsburgh. Salk believed he could create a vaccine using inactivated poliovirus—a killed version of the virus that would safely teach the immune system to recognize and fight the real thing.

It wasn’t the most glamorous approach. Many researchers were chasing live-virus vaccines, hoping for more potent immunity. But Salk was methodical. Careful. And deeply motivated by the children he saw suffering.

By 1953, he had developed a working prototype—and tested it on himself, his lab team, and even his own family.

🧪 The Largest Medical Trial in History

In 1954, Salk’s vaccine was ready for testing.

The result was the largest clinical trial the world had ever seen: over 1.8 million children took part in what became known as the Polio Pioneers study. Some received the real vaccine. Others got a placebo. Neither they nor their doctors knew which.

The results, announced in April 1955, made headlines around the world.

“SAFE, EFFECTIVE, AND POTENT,” declared front pages.

The Salk vaccine reduced polio incidence by over 90% in vaccinated groups. Within weeks, a nationwide rollout began.

🙏 A Moment of Global Relief

The public reaction was euphoric. Church bells rang. Parents wept. People hugged strangers in the street.

Dr. Thomas Francis Jr., who led the trial evaluation, called it “a victory over a dread disease.”

Jonas Salk became a national hero. When asked who owned the patent to the vaccine, he famously replied:

“There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

Production ramped up, and cases began to plummet. But the story didn’t end there.

💊 Sabin’s Oral Vaccine and the Global Campaign

While Salk’s injectable vaccine was effective, it required trained medical personnel and refrigeration—difficult in many parts of the world.

Enter Dr. Albert Sabin, a rival researcher who developed an oral polio vaccine (OPV) using a weakened live virus. It was easier to administer (just drops on the tongue), cheaper to produce, and provided community-level immunity by reducing virus shedding.

By the 1960s, most of the world adopted the Sabin vaccine as the primary tool for polio eradication.

Children lined up in schools and clinics to take “sugar cubes” laced with the vaccine—some of the most joyful medicine ever delivered.

🌍 How the World Got Better

With the help of the Sabin and Salk vaccines, polio cases began to collapse worldwide.

In 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) launched, with the goal of completely eliminating the virus—just as had been done with smallpox.

Since then:

- Polio cases have dropped by 99.9%

- Over 20 million people who would have been paralyzed are walking today

- 125+ countries have been declared polio-free

Only a handful of countries—like Afghanistan and Pakistan—still report rare, isolated outbreaks.

But the world is close. So close.

🦽 Remembering What Came Before

Today, it’s easy to take mobility for granted. We don’t see iron lungs in hospital wings. We don’t see children learning to walk again with crutches.

That’s because the vaccine worked.

“You wouldn’t know today what a terror it was,” said one survivor. “And that’s a blessing. But it’s also why we have to remember.”

✨ Why This Story Matters

Polio didn’t just disappear. It was pushed back by science, cooperation, and courage.

It took:

- Two brilliant but very different scientists—Salk, the methodical idealist, and Sabin, the fiery globalist

- Millions of parents who trusted a new medical technology

- Children who volunteered to be part of the solution

- Citizens who mailed in dimes, one at a time, to fight back

The story of polio reminds us that the world didn’t get better by accident. It got better because people worked for it—and believed in something bigger than themselves.

Our ‘When The World Got Better’ Series

- When The World Got Better: Smallpox

- When The World Got Better: Polio

- When The World Got Better: Measles

- When The World Got Better: HBV

- When The World Got Better: Hib vaccine

- When The World Got Better: mRNA vaccines

- When The World Got Better: Influenza

📚 Want to Go Deeper?

- The March of Dimes History

- CDC: Polio Elimination in the U.S.

- GPEI: The Global Fight to End Polio

- PBS: The American Experience – The Polio Crusade

Last Updated on June 30, 2025