The Near-Victory That We’re Still Fighting For

🧼 Life Before the Vaccine: Everyone Got It

If you were born before 1963, you probably had the measles.

It was almost a childhood rite of passage—an illness so common that it was simply expected. In the United States, 90% of children had measles by age 15. But make no mistake: it wasn’t just a harmless rash and fever.

Measles could be severe—even deadly. It caused high fevers, deep coughs, inflamed eyes, and a spreading rash that often covered the entire body. One in 20 children developed pneumonia. One in 1,000 developed encephalitis—a dangerous brain swelling that could cause permanent disability or death.

And one in every few thousand children who recovered from measles would, years later, develop SSPE (subacute sclerosing panencephalitis), a rare but fatal neurological disorder that slowly erased their mind and body.

“We thought of it as a routine illness,” said one nurse who worked in pediatric wards in the 1950s. “But there were always some who didn’t go home.”

📈 The Measles Epidemics

Every two to three years, epidemics swept through schools and communities. It didn’t matter if you were rich or poor, rural or urban. If one child in a class got measles, half the class might be home within a week.

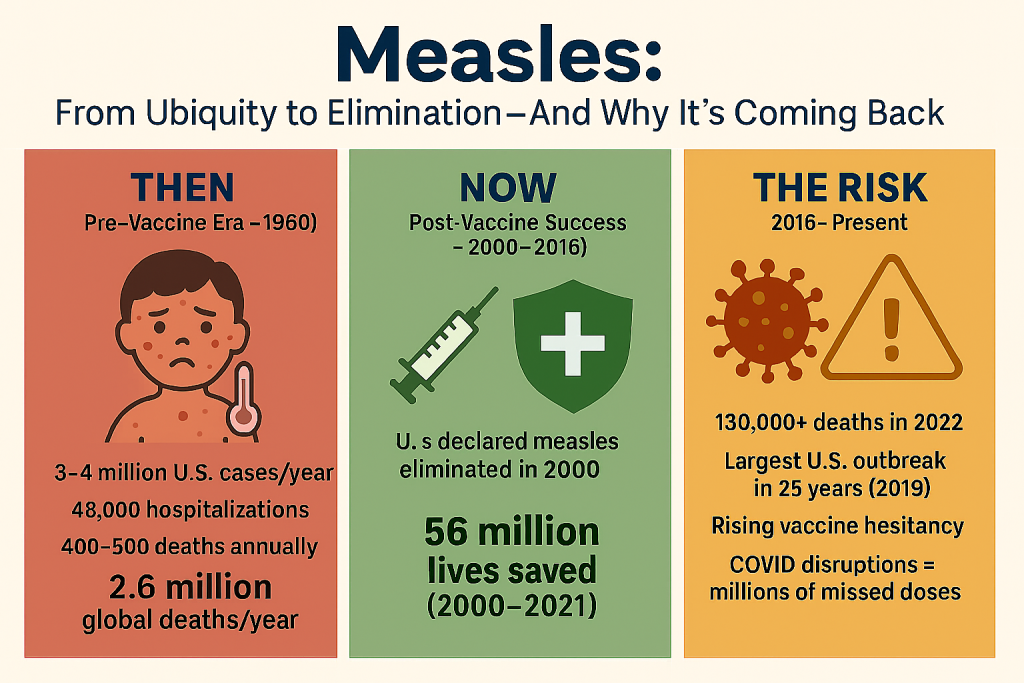

In the U.S. alone:

- 3 to 4 million people were infected every year

- 400–500 people died

- 48,000 were hospitalized

- 1,000 suffered permanent brain damage

Worldwide, measles killed an estimated 2.6 million people every year as late as the 1980s—most of them young children.

There was no treatment. Just care, quarantine, and hope.

🧬 The Scientist Who Cracked the Code

The breakthrough came from a quiet, determined virologist named Dr. John Enders, often called “The Father of Modern Vaccines.”

In 1954, Enders and his team—including Drs. Thomas Peebles and Samuel Katz—managed to isolate the measles virus from an infected child and grow it in the lab. It was a critical first step.

After years of careful attenuation—weakening the virus so it could train the immune system without causing illness—the team developed the first measles vaccine, licensed in 1963.

Enders had already shared a Nobel Prize in 1954 for his work on the polio vaccine. But he considered the measles vaccine one of his greatest achievements.

💉 The Vaccination Campaign Begins

The early version of the vaccine had some side effects, so it was soon replaced with an improved live attenuated vaccine in 1968. By the 1970s, measles cases in the U.S. were falling fast.

By the 1980s, public health officials knew that a single dose wasn’t always enough. A second dose became standard—usually given around age 4 or 5.

The result?

- In 1980, measles caused 2.6 million deaths globally

- By 2016, that number had dropped to under 90,000

That’s a 96% reduction in measles deaths—a public health triumph that often goes uncelebrated.

🌍 A Global Fight with Stunning Results

The Measles & Rubella Initiative, launched in 2001 by the WHO, UNICEF, and other partners, helped deliver billions of vaccine doses worldwide.

Thanks to mass vaccination campaigns:

- Measles deaths in Africa dropped by 92%

- Countries across the Americas, Europe, and Southeast Asia reported years without a single endemic case

- From 2000 to 2021, measles vaccination prevented an estimated 56 million deaths

And yet…

🔄 A Comeback Nobody Asked For

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States—meaning there was no continuous transmission. But it didn’t last.

By the 2010s, vaccine hesitancy began to erode hard-won progress. Fueled by misinformation and distrust, some parents began skipping the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine. Pockets of under-vaccination grew.

In 2019, the U.S. saw its largest measles outbreak in 25 years.

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted routine childhood immunizations. In 2022 alone, more than 130,000 people died of measles—most of them children.

🧠 What Makes Measles So Dangerous

Measles isn’t just dangerous because of the acute illness—it also suppresses the immune system. Scientists call it “immune amnesia.” After infection, the body literally forgets how to fight off other diseases it previously learned to handle.

Studies show that measles infection can erase 20–70% of the body’s existing immune memory.

That’s why measles outbreaks often lead to secondary spikes in pneumonia, diarrhea, and other infections—even weeks later.

✨ Why This Story Matters

The measles vaccine is one of the safest and most effective tools in all of medicine.

One shot gives over 93% protection. Two doses? 97%.

And yet we’re at risk of losing ground—not because the vaccine doesn’t work, but because we’ve forgotten what the disease was like.

The story of measles reminds us that public health victories are fragile. They’re not guaranteed. They must be renewed—generation by generation—with trust, effort, and memory.

📣 What We Can Learn

Measles showed us what global coordination could achieve.

It also shows us what happens when complacency sets in.

In a world where misinformation spreads faster than any virus, remembering our history may be the most important kind of immunity we can build.

Our ‘When The World Got Better’ Series

- When The World Got Better: Smallpox

- When The World Got Better: Polio

- When The World Got Better: Measles

- When The World Got Better: HBV

- When The World Got Better: Hib vaccine

- When The World Got Better: mRNA vaccines

- When The World Got Better: Influenza

📚 Want to Go Deeper?

Last Updated on June 30, 2025