A New Series About Vaccines That Changed Everything

Most people alive today have no memory of what it was like to live in constant fear of diseases like polio, measles, or smallpox. But just a few generations ago, these illnesses shaped entire societies. They closed schools. Crippled children. Scarred survivors. Ended lives far too young.

Then something extraordinary happened: we discovered how to stop them.

This series tells the story of those turning points—of what life was like before the vaccine, the people who fought to create it, and the quiet revolutions that followed.

It’s the story of how the world got better—one shot at a time.

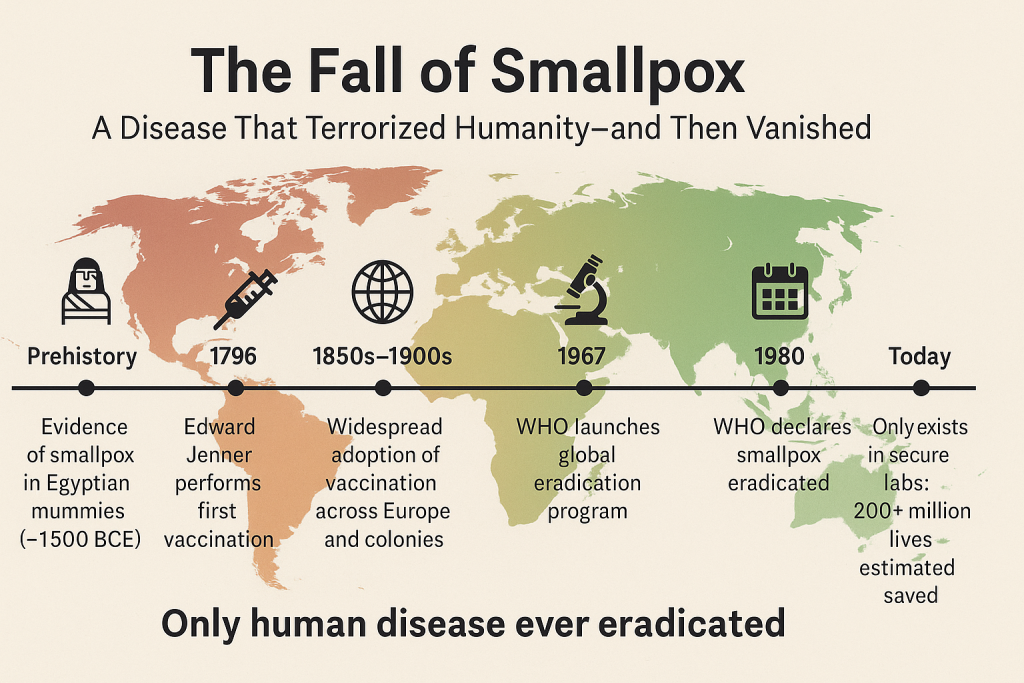

🧪 Episode 1: Smallpox

The First Vaccine—and the First Victory

😷 A Disease That Terrorized the World

Before vaccines, smallpox was one of the most feared diseases on Earth. It swept through villages, cities, continents—leaving a trail of death, disfigurement, and despair. Its telltale rash began with fever and chills, then exploded into fluid-filled pustules that covered the body. Those who survived were often left with deep scars—physical reminders of how close death had come.

But many didn’t survive. Smallpox killed about 30% of those it infected. In children, the fatality rate was even higher. The disease didn’t care about wealth, power, or borders. It struck kings and commoners alike—Queen Mary II of England, Tsar Peter II of Russia, and the Inca emperor Huayna Capac all died from it. In Europe alone, smallpox claimed hundreds of thousands of lives every year. Globally, the death toll ran into the millions annually.

“Smallpox was the most terrible of all the ministers of death,” wrote historian Lord Macaulay in the 19th century. “The havoc of the plague had been far more rapid, but the plague had visited our shores only once or twice within living memory; the smallpox was always present, filling the churchyard with corpses…”

In the Americas, smallpox played a devastating and tragic role in the conquest and colonization of Indigenous peoples. Entire communities were wiped out by a disease they had never encountered—and had no natural immunity to.

There was no cure. The only real option was isolation—if you were lucky—and praying the disease passed you by.

Until one man dared to try something new.

💡 Edward Jenner and the Cow that Changed History

In the late 1700s, a quiet English country doctor named Edward Jenner began to pay attention to a rumor.

Milkmaids, it was said, didn’t get smallpox.

Why? Because they often contracted cowpox—a mild illness passed from cows that caused blisters on the hands but no lasting harm. Jenner wondered: could cowpox be protecting them from smallpox?

In 1796, he set out to test the idea—using a method no one had ever attempted before.

Jenner took pus from a cowpox sore on the hand of a local milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes, and used it to inoculate an 8-year-old boy, James Phipps, the son of his gardener. The boy developed a low fever and a sore—but quickly recovered.

Then came the real test. Weeks later, Jenner deliberately exposed James to live smallpox.

James didn’t get sick.

It was the first recorded case of vaccine-induced immunity in human history. Jenner had proven something extraordinary: a safer disease could train the body to fight a deadlier one.

He called the technique vaccination—from vacca, the Latin word for cow.

Jenner faced skepticism. His ideas ran counter to both medical tradition and religious beliefs of the time. Some caricatured him in cartoons, imagining people who had been vaccinated sprouting cow-like features. But word spread. Doctors began replicating his work. And slowly, the tide began to turn.

🌍 A Slow but Steady Revolution

In the 1800s, countries across Europe began adopting smallpox vaccination—some through national mandates, others through public health campaigns.

- Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the French army to be vaccinated.

- The United States made smallpox vaccination a public health priority after devastating outbreaks.

- In British colonies, vaccination became widespread—though often imposed unequally and with controversy.

By the early 20th century, routine vaccination had drastically reduced smallpox deaths in wealthy countries. But outbreaks still occurred, and smallpox remained endemic in many parts of Asia and Africa. It continued to kill millions globally.

Even with vaccines available, smallpox refused to disappear—until the world decided to get serious.

🛡️ The Eradication Campaign

In 1967, the World Health Organization launched an ambitious plan: eradicate smallpox completely.

It was a radical goal. No disease had ever been wiped out before. But the smallpox vaccine had key advantages:

- It provided long-lasting immunity after just one dose

- Infections had a clear rash, making cases easy to identify

- Humans were the only host—there were no animal reservoirs

Public health teams were deployed worldwide. They vaccinated entire populations, sometimes going door to door. When outbreaks occurred, ring vaccination strategies were used: vaccinate everyone around a confirmed case to stop the spread.

The effort took a decade, thousands of workers, and extraordinary international cooperation—even during the Cold War.

Finally, in 1977, the last known natural case of smallpox occurred in Ali Maow Maalin, a hospital cook in Somalia. He survived.

In 1980, the World Health Assembly officially declared:

“Smallpox is eradicated.”

It was a sentence humanity had never been able to say about any disease before.

📉 A Disease Gone, But Never Forgotten

Smallpox was the first—and still only—human disease ever eradicated through vaccination.

Since then:

- It has saved an estimated 200–500 million lives

- No child has been born with the risk of smallpox in over 40 years

- The vaccine is no longer needed for the general population

Only two secure labs—in the United States and Russia—still hold samples of the virus for research. There is no treatment. But we don’t need one—because we stopped it from spreading in the first place.

✨ Why This Story Matters

We didn’t beat smallpox because it got weaker.

We didn’t beat it because it just “burned out.”

We beat it because people—scientists, doctors, volunteers, and communities around the world—refused to give up.

They used the tools of science. They learned from each other. They believed that prevention was possible.

And they were right.

Today, it’s easy to forget what smallpox was like. That’s the paradox of public health: its greatest successes are invisible. We don’t see the suffering that didn’t happen. The funerals that never took place. The children who lived full lives because a tiny drop of vaccine kept them safe.

But the story of smallpox reminds us:

Sometimes, the world really does get better.

Our ‘When The World Got Better’ Series

- When The World Got Better: Smallpox

- When The World Got Better: Polio

- When The World Got Better: Measles

- When The World Got Better: HBV

- When The World Got Better: Hib vaccine

- When The World Got Better: mRNA vaccines

- When The World Got Better: Influenza

📚 Want to Go Deeper?

- World Health Organization – Smallpox Eradication Facts

- CDC: History of Smallpox

- UN Chronicle: How Smallpox Was Eradicated

Last Updated on June 30, 2025